At the end of December last year, I chose to join a sub called r/FreeLuigi. My introduction to Luigi Mangione and his case was a couple weeks late because I’d checked out of news due to extreme mental fatigue from Donald Trump. I found out about him at work, hearing that his getaway included a bicycle, which honestly made me bust out laughing, saying, “That’s some far left shit!” Later, after he was caught, I did what all nerdy people do and chose to find out as much as possible about him before I made a judgement. I didn’t simply want to jump on the bandwagon. I wanted to know why—and I’m aware that a lot of people felt the same way. During this process, I went to the most logical place to find fellow supporters: Reddit. Well, logical to a woman who grew up using BBS.

Initially, the sub was a breath of fresh air from other areas of the internet that had misinformation, cutesy memes, and ill-informed psychoanalysis. Although it quickly descended into chaos with an influx of new members after the two perp walks and his first court hearing. Mods tried to fix this by creating another group for thirsting and making rules that “sexual objectification” of Luigi was not allowed. Sometime later, when a supporter received a letter from him, rules were made that letters were not to be shared for any reason. Both restrictions seemed fair at the time, as a way to protect his privacy. However, it quickly grew into a bigger monster than one could have ever expected.

The moderators of this sub, as well as select groups on other social media platforms, chose to forbid any objectification of Luigi Mangione. This is, in itself, not a problem and demonstrates an egalitarian viewpoint, at least on the surface. Historically, women have experienced objectification by men in a way that ignored our needs, feelings, thoughts, and basic humanity. Up until roughly 75 years ago, women were still thought of as property.

Female objectification, as described through the male gaze.

However, what about women’s objectification of men? What is the issue here?

On the Nature of Male Sexual Objectification

Objectification of women by men is a real issue in multiple cultures, even in modern day, and can be severely damaging to us psychologically. Though things have gotten significantly better, female objectification remains an issue.

As women have moved up the ladder and gained more agency, male objectification has increased. Though women are still, for the most part, hesitant to express that objectification publicly, we can do so freely with each other in certain designated spaces. Even in those spaces, objectification is not typically demonstrated in the way many men do (i.e., as an act of dominance or to gain status over other men). Male objectification in women’s spaces is typically a bonding activity and frankly superfluous. This is not to diminish the effects of objectification—it’s simply meant to describe the differences between how women and men engage in this behavior.

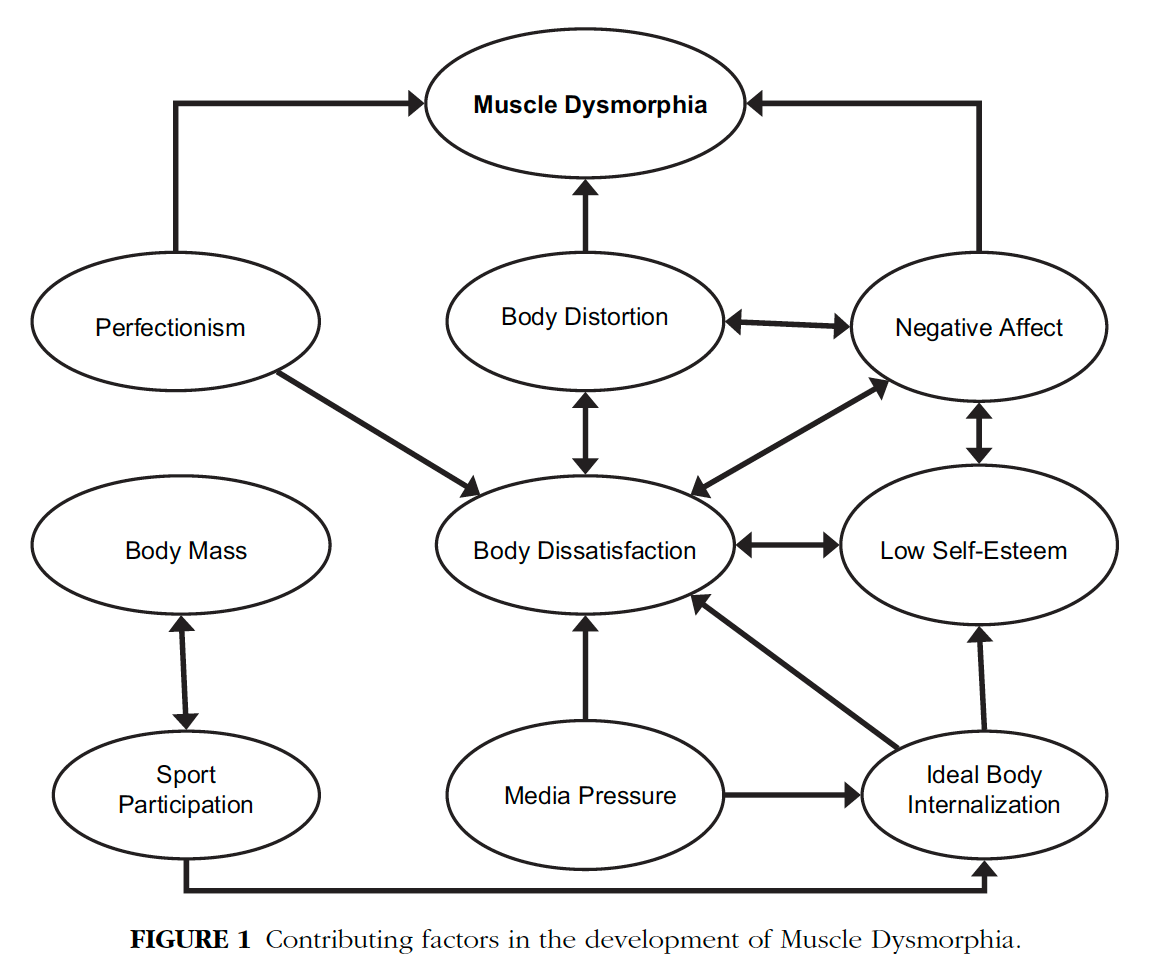

Because of these reasons, male sexual objectification does not bring up the same historical issues. This makes the dynamics different for men on a psychological level. Though in relatively low instances, male objectification has been slowly increasing. Muscle dysmorphia, a psychological condition experienced mainly by men, contributes to eating disorders and other harmful effects. Grieve suggests a model describing nine variables that come together to influence the development of muscle dysmorphia: body mass; media influence; ideal body internalization; low self-esteem; body dissatisfaction; health locus of control; negative affect; perfectionism; and body distortion.1 Researchers have termed this the “Adonis Complex.”2 I am not comfortable psychoanalyzing Luigi. However, it is obvious that he did experience a glow up after high school. It’s likely that body issues affected Luigi, as they do many men, to some degree. In 1993, Psychology Today surveyed their readers on male body image.3 Over 1,500 people responded, with nearly twice as many women answering than men. This is an important detail. According the article about this research:

“From hairline to penis size, men believe their specific physical features strongly influence their personal acceptability by women (…) A significant subset of women who are financially independent and rate themselves as physically attractive place a high value on male appearance. This new and vocal minority unabashedly declares a strong preference for better-looking men.”

Feminism has improved women’s social and financial stature, thus providing more choice for heterosexual women in the dating market. But, in a time when women own our sexuality and deliberately engage in self-objectification regularly, what if men, in the shift to become our equals, now experience some of that dehumanization we escaped? At the present time men are rarely studied for the psychological trauma that increasing objectification has on them. The effects of sexual objectification will remain an issue and research is likely to increase in the future, as men are only starting to experience the consequences of the past while women work to keep pace. This, unfortunately, is a natural affect of our egalitarian society evening out. Women would always eventually appropriate any and every aspect of the stereotypical masculine, including objectification. It is essential for us to create the same types of safe places for men that we did for women, and discuss the increasing pressure for men to engage in looksmaxxing; specifically in a world where men have not packed their own parachute.

Based on the biopsychosocial model prevalent in psychology, Grieve’s hypothetical model of Muscular Dysmorphia demonstrates a mix of outside and internal influences (including social, cultural, and psychological factors) that interact to influence the development of MD.

As one can see, Grieve indicated that some of the factors that affect women might also affect men. Men, however, present body dysmorphia differently. Though the research is limited on male body dysmorphia, studies conducted since the initial discussion of this model indicate that men with body dysmorphic disorders tend to be more concerned with muscularity than thinness (body mass). 4 5 6 7 Additional studies proved other factors in this model: body dissatisfaction, 8 9body dysmorphia,10 11 12; media pressure13; sociocultural expectations,14 1516; and low self-esteem. 1718 Taken together, the cited studies indicate significant evidence for several factors in Grieve’s original model. Research also verifies that body image insecurity among men is growing, and has been since the 1990s.

Do women contribute to this rise in male body insecurity?

Physically, men have their own perception of what they think women sexually desire. 19 Personally, the photo below was not the one that grabbed my attention. Not because there aren’t women who find muscular men attractive. Rather, that’s not my type and never will be. I don’t find muscular men attractive.

This photo below is the one that caught me (and many others):

I guess some women are just into unkempt, dirty men who look like they’ve been awake for 48 hours straight. 🤷🏻♀️

In fact, in a study that asked men to choose what they thought was women’s ideal male body from a set of pictures, men chose male body types that were significantly more muscular and leaner than the body types women chose.20 Men apparently believe that women would rather a date with Chad nerd Luigi than feral nerd Luigi (“nerd” is a non-negotiable descriptor here). This is a consistent finding since as early as 1985,2122 which indicates to me the only logical conclusion here: men (of any sexuality) find muscular men a lot more attractive than women do.

Meanwhile, women are looking for the men who smell straight up of overwhelming pheromones:

Sorry for getting off topic there these men make my brain go numb. I’ll try to

stop objectifying men in my essay about objectifying men.

Erm—in fact, Luigi essentially said himself in a letter to a (female) supporter that he looked like shit in his mugshot. Mind you, this is the photo that wet countless pussies, unleashed thousands of thirst videos and memes, and (yes) inspired erotic fan fiction. But, while women are much more comfortable with objectifying men now than they ever have in history, that doesn’t mean that we’ve gained the upper hand.

Within the Luigi fandom, different communities have followed in r/FreeLuigi’s footsteps to forbid objectification or sexual comments about Luigi. Meanwhile the women who are sexualizing him tend to be fantasizing out loud to each other that they’d like him to objectify them.

Some researchers have posited that men are more sensitive to how other men view them. 17 18 “It’s other men who are important to American men (...) Masculinity is largely a homosocial enactment.”23 Kimmel goes on to say, regarding performance of masculinity, “We are under the constant careful scrutiny of other men. Other men watch us, rank us, grant our acceptance into the realm of manhood.” Thus, a large muscular and lean body may signal degree of masculinity and indicate where a man lies in that hierarchy rather than an interest in attracting women. 2425 In fact, a study in 2017 used eyetracking to assess the male objectifying gaze on photos of other men.26 This method allowed researchers to detect the location and the duration of (literal) gaze to different parts of men’s bodies. Male participants were divided into two test groups that would evaluate for physical attractiveness or perceived personality. The control group contained a mix of genders. Results reinforced previous findings that those focused on physical attractiveness look at faces for less time and look at other body parts (eg, chests, arms, and stomachs) for more time than personality-focused participants. Based on past studies, this indicates a degree of dehumanization. Researchers also found that both men and women focused on the same body parts, which may indicate a cultural aspect of objectification more than anything.

Additionally, because physical appearance and the idea of masculinity are inextricably linked (as with physical appearance and femininity), it’s not a stretch to assume this type of objectification from other men can affect a man’s perception of themselves as a man.

“Our efforts to maintain a manly front cover everything we do” (Kimmel, 2008).

Think Luigi’s infamous perp walk:

Some in the neurodiverse community have speculated Luigi is one of us…. Which would make this act even more tedious, as he would be high masking for both masculinity and ND.

Here, he seemingly realizes his head is down and quickly jerks it up, as if to avoid showing weakness, thus lack of masculinity. Additionally, he is surrounded by men, all of them are in control of him, holding guns. He will be turned into a number at the detention center he is being transferred to (#52503-511) and will be expected to recite it instead of his own name. Here, Luigi is an object, a trophy to tout for the media. His outfit, silence, restraints, and lack of bulletproof vest that others seem to be wearing, make it clear that he is unimportant in comparison. While objectification is typically associated with sexuality, it need not only be sexual in nature. Objectification is merely demonstration of a power dynamic. This dehumanization technique used within the prison systems is similar to those used on enslaved people in the Antebellum South as well as those targeted during the Holocaust. It is meant to denote ownership.

Consider if the people surrounding Luigi had been women. While it’s true that we are just as capable as men in careers like this, the reaction for the female cops and for Luigi might have been much different, as the patriarchal power dynamic would be thrown off.

Some Luigi fans have even pointed out that, in the clip above, he is treating a female officer more gently than he would a male officer. Personally, I think he just couldn’t do a whole lot with his hands in cuffs. Regardless, that perception, noted more than once by multiple people, reinforces our cultural attitude of the male/female power dynamic so ingrained in many parts of the world.

I would like to argue that the largely male-controlled prison system is objectifying Luigi in a more disturbing and damaging way than women sitting around giggling about him having an 8-inch fat cock. Yet, for some reason, women’s adulation of Luigi is focused upon not only in media, but also in online communities. It fills the online Luigi community with fraught and utter dread. Meanwhile, few conversations include discussions of collective efforts to change the treatment of prisoners or impact healthcare reform. Weekly, the (female-majority) communities discuss the negative impact of women being attracted to or objectifying him (though this still appears to be a minor part of the overall discussion in these communities; more on that later).

And, so no rock is left unturned, depersonalized sexuality is also embedded into the performance of what masculinity should be, despite men’s personal feelings on the subject. Take, for example, this teen discussing his first sexual experience:

“I was just there for her to have sex with, not as a person (...) It was something I could talk about with other guys—and I did, but I never told the other guys I wasn’t comfortable with it. You can never say that as a guy. It’s got to be great. It’s not even ‘It’s got to be great,’ it is great. Period.” ‘Liam,’ 18 years (Orenstein, 2020).

When a man actually is dehumanized and essentially raped by a woman, the shame is not something he can talk about with other men—because women are meant to be those with lower status. To not like this would be to lower oneself to the status of a woman. Again, objectification is demonstration of a power dynamic and ownership. Men are expected to be in that ownership role. Neither men nor women can escape their roles in this weird patriarchal structure that has been created which ALL of us hate, no matter what they actually do. Therefore, rape by a woman is actually perceived as impossible by some men. Many legal definitions of rape only include penetration.

It’s easy to understand then, that the depersonalization of sex and dehumanization of others is essential to the idea of what it means to be dominant, which is seen as masculine (regardless, again, of whether men actually feel this way, it’s embedded into a patriarchal ideal that took thousands of years to fine tune). Women can dehumanize men, but in the majority of situations, any attempts for women to dehumanize men on the same level is typically met with laughs—this is seen as a way to impress other men and signal masculinity. This social dynamic cannot be said for women. In fact, men themselves are the ones laughed at if this happens. Again, this is not to say women do not objectify men. This is to say the problem is in the ways men silence and judge each other.

Subscribe to be alerted when I publish more articles.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Kimmel, 2008 In Guyland: The Perilous World Where Boys Become Men. Harper.

Orenstein, P. (2020). Boys and sex: Young men on hookups, love, porn, consent, and navigating the new masculinity. Harper.

Great analysis! I feel like a lot of male-targeted sexual started as a half-joke, almost as a way to “get back” at men for making women feel uncomfortable, but it has definitely gone way too far. It’s ironic how it inadvertently ended up propping up patriarchal views of masculinity and what it means to be a “real man” or whatever. Some of the comments I’ve seen online about Luigi are WILD. Like, beyond the point of reason. Women have gone insane projecting their desires and shadow selves onto him, and they barely even know what his actual voice sounds like. It makes no sense to me. Thank you for taking the time to call it out as it is.